Aloha & Welcome

Mahalo for taking the time to learn more about our Hawaiian culture.

I have found many books and web pages filled with conflicting information. If you come across anything that your not sure of and would like to bring to my attention please don't hesitate in reaching out to me. I appreciate your help and assistance. This book was built with the hopes to share. This mean I share with you and you share with me.

Much of what you read come from numerous resources available today. Lessons and stories learned and shared from my background in Hawaiian Studies, lessons and stories shared by my ohana (family), na kupuna (elders) and na kumu (teacher). The numerous books and web sites, as well from talking story with people who understand and help to perpetuate our Hawaiian culture. Mahalo!

These pages continually change and evolve through the support of the many comments, questions and inspiration from the people I meet along this journey we call "LIFE".

Enjoy!

Mahalo nui loa,

Michaela Lehuanani Larson

Please send photos and comments

Mahalo for taking the time to learn more about our Hawaiian culture.

I have found many books and web pages filled with conflicting information. If you come across anything that your not sure of and would like to bring to my attention please don't hesitate in reaching out to me. I appreciate your help and assistance. This book was built with the hopes to share. This mean I share with you and you share with me.

Much of what you read come from numerous resources available today. Lessons and stories learned and shared from my background in Hawaiian Studies, lessons and stories shared by my ohana (family), na kupuna (elders) and na kumu (teacher). The numerous books and web sites, as well from talking story with people who understand and help to perpetuate our Hawaiian culture. Mahalo!

These pages continually change and evolve through the support of the many comments, questions and inspiration from the people I meet along this journey we call "LIFE".

Enjoy!

Mahalo nui loa,

Michaela Lehuanani Larson

Please send photos and comments

|

Dedication

To my kupuna (elders/grandparents), who for years have freely shared their stories. They teach respect, responsibility, and aloha, love. Stories spoken with deep meanings and intense expressions. When I would ask "why I never heard this story before" my Tutu would say “no sense share, nobody listens, they no care”, to me this is sad. Mahalo Tutu for sharing your many stories with me. I will try my best not to let your stories be forgotten or lost. Kumu (teachers) who lovingly share their knowledge selflessly. Teachers who share the importance of knowledge. To achieve our dreams and our goals. Teachers who inspire and motivate. Mahalo for giving freely beyond the classroom. Mahalo nui loa, Akua! |

Your journey begins here...

These pages are not complete and not in this order.

In progress... Mahalo!

- Dedication 4

- Acknowledgment 7

- Introduction 10

- Ekahi - One 12

- Kailua - “Two Seas” 12

- Home of Hawaiian Royalty 12

- Your journey begins here! 13

- Ahu’ena Heiau “temple of the burning altar”. 13

- Kamakahonu Bay - Eye of the Turtle 16

- Kailua Pier 17

- Kaiakeakua - Sea of the Gods 18

- Mokuaikaua Church - “land eaten by man" 19

- Hulihe'e Palace 21

- Kona Inn 22

- Hale Halawai 23

- Legend or My Story on this page. 24

- Kauakaiakaola, Luakini Heiau - Sacrificial Temple 25

- Holualoa Bay 26

- Kamoa Point - Keolonahihi - Sports Complex 27

- Keolonahihi - Sports Complex 28

- La'aloa - Magic Sands 29

- Kahalu'u 30

- Saint Peters Church - The Little Blue Church 31

- Ku’e Manu - Dedicated to Surfing 32

- Pa'okamenehune 33

- Hapai Ali'i & Ke'eku Heiau 34

- Keauhou Bay - Tide or Current of Constant Change 36

- Kamehameha the Third - Kauikeaouli 36

- PICTURE HERE 36

- Pu'u O Hau - Red Hill and the Face of Pele 46

- The legend of Ohio, Lehua and Madam Pele

- Kealakehua Bay 49

- PICTURE HERE 49

- Captain Cook 51

- PICTURE HERE 51

- Turmoil 52

- More visitors 53

|

Acknowledgment Maggie Brown, owner and operator of Body Glove Cruises Hawaii. Maggie is Hanai (with affection) Aunty to many young people coming to Kona looking for a new adventure. These travelers quickly realizing that they need to find work to support their adventure. They find their way to the Body Glove Office and Ms. Maggie and her son Michael. Of course this is a relationship that supports each other, we need each other. My hope is that these pages will provide a deeper appreciation for our islands, it's history and the people who call Hawaii their home. Me Ke Aloha Pumehana, Michaela Lehuanani Ikaika Larson |

Introduction

Hawaii My Home

Each Island has its own feel, its own personality and charm.

Maui is fun and cheerful!

Oahu has a strength of power that draws people who are driven and enjoy modern amenities. Don’t get me wrong Oahu too has it’s sacred places and spirit. I’m giving you a my observation and feeling.

Kauai is definitely the honeymooners island, not just because it rains all the time which keeps lovers indoors. Kauai is beautiful. An understanding that this island has a deep sense of place.

Moloka’i is roots. A connection to “mana”, the source, energy. When you go to Molokai you have stepped back lifetimes to a place that forces you to believe, God exists. You feel the presence of power.

Lanai the little one. Lanai is country, the whole island. Rest and relax is what you do when you go to Lanai. Rest and relax. You can't get away from the craziness. Just let it be.

Hawaii Island the Big Island is young and powerful. Hawaii Is for the adventurist filled with natural beauty and energy. You will find peace and a sense of place.

Word translations - These word translations are commonly used to understand the essence of our thoughts and words. This will help you while reading this material.

Mana: Supernatural or divine power, mana, miraculous power; a powerful nation, authority; to give mana to, to make powerful; to have mana, power, authority; authorization, privilege; miraculous, divinely powerful, spiritual; possessed of mana, power.

Kahuna: Priest, sorcerer, magician, wizard, minister, expert in any profession (whether male or female); in the 1845 laws doctors, surgeons, and dentists were called kahuna.

hā: To breathe, exhale; to breathe upon, as kava after praying and before prognosticating; breath, life. Hā ke akua i ka lewa, god breathed into the open space.

uka: Inland, upland, towards the mountain, shoreward (if at sea); shore, uplands (often preceded by the particles i, ma.

kai: Sea, sea water; area near the sea, seaside, lowlands; tide, current in the sea; insipid, brackish, tasteless. I kai, towards the sea.

Makai: on the seaside, toward the sea, in the direction of the sea. O kai, of the lowland, of the sea, seaward. up the mountain, mountain, in the direction of the mountain.

Mauka: up the mountain, mountain, in the direction of the mountain.

Kupuna: Grandparent, ancestor, relative or close friend of the grandparent's generation, grandaunt, granduncle.

Kumu: Teacher, tutor, manual, primer, model, pattern. Kumu alakaʻi, guide, model, example. Kaʻu kumu, my teacher. Kumuhoʻohālike, pattern, example, model. Kumu hula, hula teacher. Kumu kuʻi, boxing teacher. Kumu kula, school teacher. Kumu leo mele, song book. Kumu mua, first primer. Beginning, source, origin; starting point of plaiting. hoʻo.kumu To make a beginning, originate, create, commence, establish, inaugurate, initiate, institute, found, start.

Kahuna: Priest, sorcerer, magician, wizard, minister, expert in any profession (whether male or female); in the 1845 laws doctors, surgeons, and dentists were called kahuna.

hā: To breathe, exhale; to breathe upon, as kava after praying and before prognosticating; breath, life. Hā ke akua i ka lewa, god breathed into the open space.

uka: Inland, upland, towards the mountain, shoreward (if at sea); shore, uplands (often preceded by the particles i, ma.

kai: Sea, sea water; area near the sea, seaside, lowlands; tide, current in the sea; insipid, brackish, tasteless. I kai, towards the sea.

Makai: on the seaside, toward the sea, in the direction of the sea. O kai, of the lowland, of the sea, seaward. up the mountain, mountain, in the direction of the mountain.

Mauka: up the mountain, mountain, in the direction of the mountain.

Kupuna: Grandparent, ancestor, relative or close friend of the grandparent's generation, grandaunt, granduncle.

Kumu: Teacher, tutor, manual, primer, model, pattern. Kumu alakaʻi, guide, model, example. Kaʻu kumu, my teacher. Kumuhoʻohālike, pattern, example, model. Kumu hula, hula teacher. Kumu kuʻi, boxing teacher. Kumu kula, school teacher. Kumu leo mele, song book. Kumu mua, first primer. Beginning, source, origin; starting point of plaiting. hoʻo.kumu To make a beginning, originate, create, commence, establish, inaugurate, initiate, institute, found, start.

Mauka to Makai

From the Mountain to the Sea

Kailua-Kona

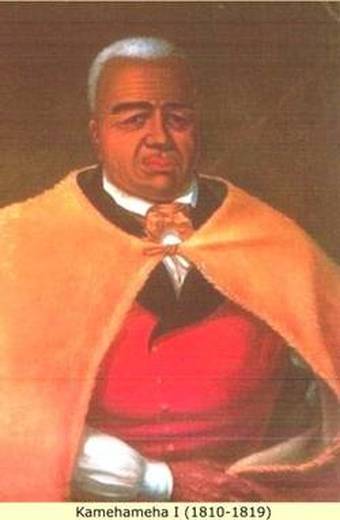

Over 200 years ago Kailua Kona was the center of political power throughout Hawai'i. This is the place where Kamehameha the Great chose Kailua-Kona to spend his golden years.

Ahuena Heiau

Ahu’ena Heiau “temple of the burning alter” on May 8, 1819 Kamehameha the Great passes away.

Three momentous events occurred here in Kailua-Kona, at Ahuena Heiau which established the temple as one of the most historically significant sites in all of Hawaii:

1. In the early morning hours of May 8, 1819 King Kamehameha the Great dies at Ahuena Heiau.

2. A few months following the death of Kamehameha, Liholiho one of the Kings many sons, becomes King Kamehameha the Second. This was a time of many changes, a time of political and religious turmoil. Queen Ka’ahumanu said to be the favorite Queen of Kamehameha, and the young Kings mother Queen Keapuokalani, convinces the young King to sit with them and have a meal which at this time was kapu, forbidden. This was one of the many acts following the passing of Kamehameha which broke the ancient kapu system. The kapu was a highly defined regime of laws that provided the framework of the traditional Hawaiian government and life of the people. Life in Hawaii was never the same. Political and religious turmoil broke out which divided the people.

3. On April 4, 1820, the first Christian missionaries from New England arrive in Kailua-Kona. They were granted permission to come ashore on a rock cropping which they said resembled Plymouth Rock. The missionaries dubbed the rock cropping the “Plymouth Rock of Hawaii”. The Queen regent Ka’ahumanu embraces the missionaries and becomes a Christian follower and an advocate to their cause to Christianize the Hawaiian people. This was the beginning of the end of a great nation.

Ahuena Heiau was designated a National Historic Landmark, December 29, 1962 and the Hawaii State Register of Historic Places, July 17, 1993

The Ahu'ena Heiau (recently restored) is the religious temple that served Kamehameha the Great when he returned to the Big Island in 1812. The center of political power in the Hawaiian kingdom during Kamehameha's golden years, his biggest advisors gathered at the heiau each night.

Not until the mid-1970s, over 150 years after these historical events unfolded, was an accurate restoration project under taken. A community-based committee Ahu'ena Heiau Inc., formed in 1993 to permanently guide the restoration and maintenance of this national treasure.

1. In the early morning hours of May 8, 1819 King Kamehameha the Great dies at Ahuena Heiau.

2. A few months following the death of Kamehameha, Liholiho one of the Kings many sons, becomes King Kamehameha the Second. This was a time of many changes, a time of political and religious turmoil. Queen Ka’ahumanu said to be the favorite Queen of Kamehameha, and the young Kings mother Queen Keapuokalani, convinces the young King to sit with them and have a meal which at this time was kapu, forbidden. This was one of the many acts following the passing of Kamehameha which broke the ancient kapu system. The kapu was a highly defined regime of laws that provided the framework of the traditional Hawaiian government and life of the people. Life in Hawaii was never the same. Political and religious turmoil broke out which divided the people.

3. On April 4, 1820, the first Christian missionaries from New England arrive in Kailua-Kona. They were granted permission to come ashore on a rock cropping which they said resembled Plymouth Rock. The missionaries dubbed the rock cropping the “Plymouth Rock of Hawaii”. The Queen regent Ka’ahumanu embraces the missionaries and becomes a Christian follower and an advocate to their cause to Christianize the Hawaiian people. This was the beginning of the end of a great nation.

Ahuena Heiau was designated a National Historic Landmark, December 29, 1962 and the Hawaii State Register of Historic Places, July 17, 1993

The Ahu'ena Heiau (recently restored) is the religious temple that served Kamehameha the Great when he returned to the Big Island in 1812. The center of political power in the Hawaiian kingdom during Kamehameha's golden years, his biggest advisors gathered at the heiau each night.

Not until the mid-1970s, over 150 years after these historical events unfolded, was an accurate restoration project under taken. A community-based committee Ahu'ena Heiau Inc., formed in 1993 to permanently guide the restoration and maintenance of this national treasure.

Kamakahonu Bay - Eye of the Turtle

Kamakahonu Bay Eye of the turtle, for a turtle shaped rock located near the bay.

Kamakahonu Bay

Kamakahonu (eye of the turtle) in the ahupua'a of Lanihau at Kailua, Kona on the island of Hawaii. Kamakahonu has been called one of the most historical sites in all of Hawaii. It was here that Kamehameha the great spent his last years and here where he died. It was here that a feast was held to mark the overthrow of the kapu system and Hawaii was changed forever.

Kamakahonu (eye of the turtle) in the ahupua'a of Lanihau at Kailua, Kona on the island of Hawaii. Kamakahonu has been called one of the most historical sites in all of Hawaii. It was here that Kamehameha the great spent his last years and here where he died. It was here that a feast was held to mark the overthrow of the kapu system and Hawaii was changed forever.

Kailua Pier

Kailua Pier first American congregational missionaries arrive from New England in 1820 and were granted permission to come ashore, Asa Thurston and Hiram Bingham set foot on a landing area which resembled Plymouth Rock; they dubbed it the Plymouth Rock of Hawaii.

Kaiakeakua - Home to the Ironman Triathlon

Kai’a’ke a’kua Beach – Sea of the Gods Ironman World Triathlon.

From 1880 to 1956, Kaiakeakua Beach was used to load cattle onto ships headed to Honolulu. Using specially trained horses, skilled cowboys would lasso a cow on the beach, pull it out into the water to have the horse swim it to a whaleboat. The men on the whaleboat would lash the cow to it and row it to an anchored ship. Prior to 1900, Kaiakeakua Beach extended to Hulihe'e Palace.

The small sandy corner of the pier is famous for being the start line of the Ironman World Triathlon. When it gets closer to race day, you can find triathletes in training along the swim course throughout the day. The depth of the water gradually slopes down to about fifty feet. Occasionally you can spot dolphins and rays while swimming the course. The buoys line the course at 1500 meters, one-quarter, one-half, three-quarter, one mile and 1.2 miles.

The small sandy corner of the pier is famous for being the start line of the Ironman World Triathlon. When it gets closer to race day, you can find triathletes in training along the swim course throughout the day. The depth of the water gradually slopes down to about fifty feet. Occasionally you can spot dolphins and rays while swimming the course. The buoys line the course at 1500 meters, one-quarter, one-half, three-quarter, one mile and 1.2 miles.

Mokuaikaua Church

First Missionary's Arrive

The congregation was first founded in 1820 by Asa and Lucy Goodale Thurston, from the first ship of American Christian Missionaries, the brig Thaddeus. They were given permission to teach Christianity by King Kamehameha II, and the Queen Regent Kaʻahumanu. After the royal court relocated to Honolulu, they briefly moved there. In October 1823, they learned that the people of Kailua-Kona had developed an interest in the new ways and had erected a small wooden church. The first structure on the site was made from Ohiʻa wood and a thatched roof, on land obtained from Royal Governor Kuakini across the street from his Huliheʻe Palace. The name moku ʻaikaua literally means "district acquired by war" in the Hawaiian language, probably after the upland forest area where the wood was obtained. After several fires, the present stone structure was constructed, partially from stones recycled from a nearby Heiau (ancient temple of the Hawaiian religion), from about 1835 to 1837. The interior is decorated with Koa wood.

Hulihe'e Palace

Hulihe'e Palace

Hulihe’e Palace built in 1838 by Governor John Adams Kuakini as his primary residence.

The Hulihe’e Palace was built by John Adams Kuakini, Governor of the island of Hawaiʻi during the Kingdom of Hawaii until his death in 1844. The palace was has handed down to his family until it was later sold to King Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani. Kalākaua renamed the palace Hikulani Hale, which means “House of the Seventh ruler,” referring to himself, the seventh monarch of the monarchy that began with King Kamehameha I. In 1885, King Kalākaua had the palace plastered over the outside to give the building a more refined appearance. After Kalākaua's death it passed to Kapiʻolani who left Huliheʻe Palace to her two nephews, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole Piʻikoi and Prince David Kawānanakoa. In 1927 the Daughters of Hawaiʻi, a group dedicated to preserving the cultural legacy of the Hawaiian Islands, restored Huliheʻe Palace and turned it into a museum. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places listings on the island of Hawaii in 1973.

Kona Inn

Kona Inn built in 1928 and was such a popular place to visit because it was the first place to provide indoor plumbing, a big deal back in the day. A bi-weekly cargo ship would bring passengers to Kailua-Kona to stay at the Kona Inn. Kona Inn stopped housing guests in 1976. Today the Kona Inn is a boutique shopping mall.

Hale Halewai

Hale Halawai First District courthouse, and jailhouse. Today Hale Halawai is a community center. Popular for our traditional Hawaiian luau, Hawaiian celebrations.

Kauakaiakaola, Luakini Heiau

Sacrificial Temple

A priest named Pa’ao, a tall fare skinned man who came from a distant land strategically planned and implemented the Kapu system which included human sacrafice. (picture comming soon)

Holualoa Bay & Kamo'a Point

Kamoa Point and Keolonahihi

Queen Keakealani-wahine 1640 - 1695, was the 20th Aliʻi Aimoku of Hawaii from 1665 - 1695. She was the sovereign queen or chieftess of The Big Island. She was born the daughter of Queen Keaka-mahana, 19th Alii Aimoku of Hawaii, by her husband and cousin, Alii Iwikau-i-kaua, of Oahu. She succeeded on the death of her mother, 1665. She married first her first cousin, Alii Kanaloa-i-Kaiwilena Kapulehu, son of Alii 'Umi-nui-kukailani, by his wife, Alii Kalani-o-Umi, daughter of Kaikilani, 17th Alii Aimoku of Hawaii. She married second her half-brother, Alii Kane-i-Kauaiwilani, son of her father, Alii Iwikauikaua, of Oahu, by his second wife, Kauakahi Kua'ana'au-a-kane. She married third Kapa'akauikealakea. She had a son Keawe-i-Kekahiali'iokamoku by Kanaloa-i-Kaiwilena Kapulehu, who would succeed her as the 21st Alii Aimoku of Hawaii. She died ca. 1695, having had issue, two sons and two daughters.

Keolonahihi - Sports Complex

Oral traditions suggest that the Hōlualoa Royal Center was constructed as early as A.D. 1300 by the Chiefess Keolonahihi and her husband Aka. Keolonahihi, either the daughter or niece of Pa'ao, constructed the complex at Kamoa. These sites included the women's features (Keolonahihi Heiau, Hale Pe`a, and Palama), the sports heiau (Kanekaheilani), and the grandstand at Kamoa Point to view the surfing and canoeing events in Hōlualoa Bay. (Pa`ao brought the Ku religion, along with a highly stratified social system, to Hawai'i from Kahiki, circa A.D. 1300.) Much of the site's history relates to the occupation of the Royal Center by Chiefess Keakamahana and her daughter, Chiefess Keakealaniwahine, in the 17th Century. These two women were the highest‐ ranking ali`i of their dynastic line and generation. The residence of Keakamahana and Keakealaniwahine is believed to be the large walled enclosure on the mauka side of Ali`i Drive. Kamehameha lived with his mother Kekuiapoiwa II and his guardians, Keaka and Luluka, at Pu'u in Hōlualoa during the rule of Kalani`ōpu`u. At Hōlualoa, Kamehameha learned to excel in board and canoe surfing (circa 1760s to early 1770s.) Later, Kalani`ōpu`u took Kamehameha to Ka`u and there is no evidence that Kamehameha maintained a residence at Hōlualoa during his reign. Instead, Kamehameha used Keolonahihi for religious purposes; after his rise to power, he stored his war god, Kukailimoku, at Hale O Kaili in the Hōlualoa Royal Center.

La'aloa - Magic Sands

La'a loa means "very sacred" also known as "Magic Sands" or "White Sands Beach", the official name is "Laʻaloa Beach County Park". During calm weather, it is one of the only fine white sandy beaches in the Kailua-Kona area. It is also sometimes called "Disappearing Sands", since the sand is washed out in a storm several times a year.

Haukalua

Haukalua was used as a leaping point for the spirits to find the underworld. Several Archaeological sites are in the area. The ruins of haukalua Heiau (an Ancient Hawaiian temple) are on a point just south of the beach, at the parking lot which was added in 2000. The stone structure was cleared and restored, and a small ceremonial platform (lele) constructed by descendants of the people who lived in this area for hundreds of years..

Kahalu'u

One of the best places to learn to surf and snorkel.

Saint Peters Church - The Little Blue Church

St. Peters Church sits on old Kahuna’s temple.

Ku'e Manu - Dedicated to Surfing

Ku'emanu Heiau, Big IslandLocated on the Big Island's western shore, about 5 miles (8 km) south of Kailua-Kona, Ku'emanu Heiau is believed to have been devoted to surfing. It was used to pray for good surfing conditions and to observe surfers offshore. It stands opposite of an excellent surfing break, which is popular up until today.

Its stone platform is about 100 feet long and 50 feet wide. On top of the foundation sits an upper stone terrace. There is a stone water pool on one side of it which could have been used for bathing or rinsing off saltwater after coming out of the ocean.

Its stone platform is about 100 feet long and 50 feet wide. On top of the foundation sits an upper stone terrace. There is a stone water pool on one side of it which could have been used for bathing or rinsing off saltwater after coming out of the ocean.

Pa'okamenehune

(photo and story comming soon)

Hapai Ali'i & Ke'eku Heiau

These two heiau have been reconstructed by Kamehameha Schools in 2007. Hapaiali'i Heiau is believed to date back to the 1400s (carbon dating indicates that it was built between 1411 and 1465). During the restoration process, archaeologists discovered that Hapaiali'i Heiau served as a solar calendar. One can accurately mark the passing of the seasons when standing behind the center stone on the heiau top platform and aligning it with various other points on the heiau. On the winter solstice the sun sets directly over the southwest corner of the platform-like structure. And at the summer solstice, it sets over the northwest corner of the structure. The platform measures 150 feet by 100 feet, and during high tide, it is surrounded by water. Historians believe it took thousands of commoners about a decade to maneuver the rocks into place and build the platform. When Hapaiali'i was reconstructed in 2007, with the help of modern machinery, it took just four month to recreate the heiau. A plaque in front of Hapaiali'i Heiau reads: Literally translated means "elevated chiefs." It was also said that the ali'i women would hanau or give birth at this heiau to instill the great mana or spiritual power within their child.

At the adjacent Ke'eku Heiau, it is believed that it is the place where invading Chief Kamalalawalu of Maui was sacrificed after being defeated by Chief Lonoikamakahiki in the 16th century. It is said that this heiau was built by a Ma'a, a kahuna (priest) of Maui, who left for Kaua'i later.

A heiau, or temple, is a pre-christian place of worship. Its age has been recorded as prehistoric.

HE WAHI MO‘OLELO – A COLLECTION OF TRADITIONS AND HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS FROM THE KAHALU‘U-KEAUHOU VICINITY IN KONA, HAWAI‘I (prepared by Kepä Maly, Cultural Historian and Resource Specialist 1 )

The following collection of land records and historical accounts describing the lands of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou, in the District of Kona, on the Island of Hawai‘i (Figure 1), was originally compiled by Kepä Maly of Kumu Pono Associates LLC in 2004. The narratives include selected traditions of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou; historical notes collected from elder kama‘äina; documentation from the Mähele ‘Äina (Land Division) of 1848-1850; conveyances of Royal Patent Grants; and proceedings of the Boundary Commission. This study seeks to provide participants in programs planning for the preservation and interpretation of resources in the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou vicinity with an overview of cultural resources, and traditional and customary practices associated with the land. Selected Mo‘olelo (Native Traditions) for the Lands of the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou Vicinity Perhaps the earliest datable traditions, describing chiefly residence and development of heiau (ceremonial structures) for the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou vicinity, are those associated with ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, dating from ca. 1525. It is recorded that ‘Umi-a-Lïloa dwelt in the distant uplands of Keauhou (near the 5,500 foot elevation), at the heiau site called Ahu-a-‘Umi (cf. Wilkes (1840), 1970; and Kanuha in Remy, 1865 (Maly, translator). The heiau, Pä-o-‘Umi, reportedly a heiau ho‘oüluulu ‘ai (a temple dedicated to the abundance of agricultural crops), was also built by ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, above Kahalu‘u Village (Stokes and Dye 1991:80, 81). Following the time of ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, we find early historians referencing several places and events within the lands of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou. The accounts are generally associated with various ali‘i, and provide glimpses of life between the 17th and 19th centuries. In the early 17th century, following his years of battles and travel, ‘Umi-a-Lïloa’s grandson, Lono-i-ka-makahiki, dwelt at Kahalu‘u (Fornander 1917:IV-II:356). Tradition credits Lono-i-ka-makahiki with building, or dedicating, of several heiau or ceremonial sites within the larger Kahalu‘u area, among them are Mäkole‘ä, two sites with the name Ke‘ekü, Kapuanoni, Keahiolo (on the boundary of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou 1st), and ‘Öhi‘amukumuku (cf. Fornander 1969, Stokes and Dye 1991, and Reinecke ms. 1930). Also in the time of Lono-i-kamakahiki, Kahalu‘u was noted for their groves of coconut trees (Kamakau 1961:56). Subsequent to c. 1730s, the chiefs Alapa‘i, Kalani‘öpu‘u, and Kamehameha I, are all associated with residency and activities in this region of Kona, with specific references to Kahalu‘u and Keauhou. Alapa‘i dwelt in the Kailua area of Kona (c. 1738) during a portion of his reign (Kamakau 1961:67). During his reign, an agricultural heiau, named Ke‘ekü, situated in the uplands of Kahalu‘u, is said to have been built (Stokes and Dye 1991:83). When discussing the heiau of ‘Öhi‘amukumuku, Stokes reported that the temple was built by either Lono-i-ka-makahiki or Alapa‘i. In 1776, Kalani‘öpu‘u is said to have restored the heiau of ‘Öhi‘amukumuku for his war god Kä‘ili, as he prepared for his battles against the forces of Maui (Kamakau 1961:85).

In his discussion on events during the later part of the reign of Kalani‘öpu‘u (c. 1776), Fornander recorded: While thus preparing material resources [for battle with Kahekili], Kalaniopuu was not forgetful of his duties to the god whom he acknowledged and whose aid he besought. This god was Kaili—pronounced fully “Ku-kaili-moku”—who from the days of Liloa, and probably before, appears to have been the special war-god of the Hawaii Mois. To ensure the favor of this god, he repaired and put in good order the Heiaus called “Ohiamukumuku” at Kahaluu, and “Keikipuipui” at Kailua, in the Kona district, and the high priest Holoae was commanded to maintain religious services and exert all his knowledge and power to accomplish the defeat and death of the Maui sovereign (Fornander 1969-II:151-152). Kalani‘öpu‘u is also credited with building the heiau of Kapuanoni, presumably during this time (Stokes and Dye 1991:71). Kamakau also reported that when Kalani‘öpu‘u was nearly 80 years old (c.1780) he was dwelling at Keauhou, so he could enjoy the surf of Kahalu‘u and Hölualoa (Kamakau 1961:105). In his discussion on the residency of Kalani‘öpu‘u in the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou area, Fornander offered the following comments: ...Kalaniopuu dwelt sometime in the Kona district, about Kahaluu and Keauhou, diverting himself with Hula performances, in which it is said that he frequently took an active part, notwithstanding his advanced age. Scarcity of food, after a while, obliged Kalaniopuu to remove his court into the Kohala district, where his headquarters were fixed at Kapaau (Fornander 1969-II:200).

At the adjacent Ke'eku Heiau, it is believed that it is the place where invading Chief Kamalalawalu of Maui was sacrificed after being defeated by Chief Lonoikamakahiki in the 16th century. It is said that this heiau was built by a Ma'a, a kahuna (priest) of Maui, who left for Kaua'i later.

A heiau, or temple, is a pre-christian place of worship. Its age has been recorded as prehistoric.

HE WAHI MO‘OLELO – A COLLECTION OF TRADITIONS AND HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS FROM THE KAHALU‘U-KEAUHOU VICINITY IN KONA, HAWAI‘I (prepared by Kepä Maly, Cultural Historian and Resource Specialist 1 )

The following collection of land records and historical accounts describing the lands of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou, in the District of Kona, on the Island of Hawai‘i (Figure 1), was originally compiled by Kepä Maly of Kumu Pono Associates LLC in 2004. The narratives include selected traditions of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou; historical notes collected from elder kama‘äina; documentation from the Mähele ‘Äina (Land Division) of 1848-1850; conveyances of Royal Patent Grants; and proceedings of the Boundary Commission. This study seeks to provide participants in programs planning for the preservation and interpretation of resources in the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou vicinity with an overview of cultural resources, and traditional and customary practices associated with the land. Selected Mo‘olelo (Native Traditions) for the Lands of the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou Vicinity Perhaps the earliest datable traditions, describing chiefly residence and development of heiau (ceremonial structures) for the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou vicinity, are those associated with ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, dating from ca. 1525. It is recorded that ‘Umi-a-Lïloa dwelt in the distant uplands of Keauhou (near the 5,500 foot elevation), at the heiau site called Ahu-a-‘Umi (cf. Wilkes (1840), 1970; and Kanuha in Remy, 1865 (Maly, translator). The heiau, Pä-o-‘Umi, reportedly a heiau ho‘oüluulu ‘ai (a temple dedicated to the abundance of agricultural crops), was also built by ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, above Kahalu‘u Village (Stokes and Dye 1991:80, 81). Following the time of ‘Umi-a-Lïloa, we find early historians referencing several places and events within the lands of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou. The accounts are generally associated with various ali‘i, and provide glimpses of life between the 17th and 19th centuries. In the early 17th century, following his years of battles and travel, ‘Umi-a-Lïloa’s grandson, Lono-i-ka-makahiki, dwelt at Kahalu‘u (Fornander 1917:IV-II:356). Tradition credits Lono-i-ka-makahiki with building, or dedicating, of several heiau or ceremonial sites within the larger Kahalu‘u area, among them are Mäkole‘ä, two sites with the name Ke‘ekü, Kapuanoni, Keahiolo (on the boundary of Kahalu‘u and Keauhou 1st), and ‘Öhi‘amukumuku (cf. Fornander 1969, Stokes and Dye 1991, and Reinecke ms. 1930). Also in the time of Lono-i-kamakahiki, Kahalu‘u was noted for their groves of coconut trees (Kamakau 1961:56). Subsequent to c. 1730s, the chiefs Alapa‘i, Kalani‘öpu‘u, and Kamehameha I, are all associated with residency and activities in this region of Kona, with specific references to Kahalu‘u and Keauhou. Alapa‘i dwelt in the Kailua area of Kona (c. 1738) during a portion of his reign (Kamakau 1961:67). During his reign, an agricultural heiau, named Ke‘ekü, situated in the uplands of Kahalu‘u, is said to have been built (Stokes and Dye 1991:83). When discussing the heiau of ‘Öhi‘amukumuku, Stokes reported that the temple was built by either Lono-i-ka-makahiki or Alapa‘i. In 1776, Kalani‘öpu‘u is said to have restored the heiau of ‘Öhi‘amukumuku for his war god Kä‘ili, as he prepared for his battles against the forces of Maui (Kamakau 1961:85).

In his discussion on events during the later part of the reign of Kalani‘öpu‘u (c. 1776), Fornander recorded: While thus preparing material resources [for battle with Kahekili], Kalaniopuu was not forgetful of his duties to the god whom he acknowledged and whose aid he besought. This god was Kaili—pronounced fully “Ku-kaili-moku”—who from the days of Liloa, and probably before, appears to have been the special war-god of the Hawaii Mois. To ensure the favor of this god, he repaired and put in good order the Heiaus called “Ohiamukumuku” at Kahaluu, and “Keikipuipui” at Kailua, in the Kona district, and the high priest Holoae was commanded to maintain religious services and exert all his knowledge and power to accomplish the defeat and death of the Maui sovereign (Fornander 1969-II:151-152). Kalani‘öpu‘u is also credited with building the heiau of Kapuanoni, presumably during this time (Stokes and Dye 1991:71). Kamakau also reported that when Kalani‘öpu‘u was nearly 80 years old (c.1780) he was dwelling at Keauhou, so he could enjoy the surf of Kahalu‘u and Hölualoa (Kamakau 1961:105). In his discussion on the residency of Kalani‘öpu‘u in the Kahalu‘u-Keauhou area, Fornander offered the following comments: ...Kalaniopuu dwelt sometime in the Kona district, about Kahaluu and Keauhou, diverting himself with Hula performances, in which it is said that he frequently took an active part, notwithstanding his advanced age. Scarcity of food, after a while, obliged Kalaniopuu to remove his court into the Kohala district, where his headquarters were fixed at Kapaau (Fornander 1969-II:200).

Keauhou

Ka Holua O Kaneaka - The Royal Slide

The primary archaeological feature of Keauhou was its monumental Hōlua Slide, a stone ramp nearly one mile in length that culminated at He`eia Bay. This is the largest and best‐preserved hōlua course, used in the extremely dangerous toboggan‐like activity. The remains are about 1290 feet long of the original that was over 4000 feet long. When in use, it was covered in dirt and wet grass to make it slippery. Contestants reached treacherous speeds on their narrow sleds by adding thatching and mats to make the hōlua slippery. When the waves were large, crowds would gather on a stone platform at He`eia Bay to watch as hōlua contestants raced against surfers to a shoreline finish.

The starting point is a narrow platform paved level, succeeded by a slightly declined crosswise platform 36‐feet long by 29‐feet wide and is followed by a series of steep descents that gave high speed to the holua sleds. Practically the whole slide is constructed of fairly large `a`a rocks, filled in with rocks of medium and small‐sized `a`a. On completion of their slides the chiefs would have their close attendants (kahu) transport them and their surfboards by canoe to a point about a mile offshore and a little to the north, from where they would ride in He`eia on the great waves of the noted surf of Kaulu.

The starting point is a narrow platform paved level, succeeded by a slightly declined crosswise platform 36‐feet long by 29‐feet wide and is followed by a series of steep descents that gave high speed to the holua sleds. Practically the whole slide is constructed of fairly large `a`a rocks, filled in with rocks of medium and small‐sized `a`a. On completion of their slides the chiefs would have their close attendants (kahu) transport them and their surfboards by canoe to a point about a mile offshore and a little to the north, from where they would ride in He`eia on the great waves of the noted surf of Kaulu.

Kamehameha the Third - Kauikeaouli

Kauikeaouli was born at Keauhou, Kona, on e island of Hawaiʻi. Many people believe that Kauikeaouli means "Placed in the Dark Clouds." Although the exact date of his birth is not known, some historians believe it was August 11, 1814. Kauikeaouli chose St. Patrickʻs Day, March 17, as his birth date after he learned about Saint Patrick from an Irish friend. His father was Kamehameha, Hawaiʻiʻs first monarch. His mother was Keōpūolani, one of the highest ranking aliʻi in Hawaiʻi.

"A Kingdom of Learning"

"Chiefs and people, give ear to my remarks! My kingdom shall be a kingdom of learning." These words, spoken by Kauikeaouli, showed he believed that education was very important. He believed education would prepare his people for the changes taking place in Hawaiʻi.

The Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School

In 1839 Kauikeaouli opened the Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School in Honolulu. He felt that future rulers must be prepared to rule a kingdom which now included both Hawaiians and foreigners. The Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School was a very special school. In 1846 its name was changed to the Royal School. Only sixteen Hawaiian children of the highest chiefly rank attended the Royal School. Five of them later became rulers of the kingdom.

Public Education

Recognizing the growing importance of education, the government took over direction and support of the schools. The Constitution of 1840 provided for free public education and required all children to attend school. By 1850 English was the language used in business, government and foreign relations. Many Hawaiians wanted to have their children learn English, hoping this would prepare them for a better future. Toward the end of Kauikeaouliʻs reign there were 423 schools in Hawaiʻi with an enrollment of over twelve thousand students. This greatly pleased Kamehameha III. His kingdom had indeed become a "kingdom of learning."

A Constitutional Government

The Declaration of Rights-1839

One of the first changes made by Kamehameha III took place in government. Kamehameha III was convinced that all people should have certain rights. In 1839 he put these rights in writing in a document called The Declaration of Rights.

The Constitution of 1840

The next year an even more important event happened. Kamehameha III granted his people laws which, for the first time, explained in writing how the government would be run. These special laws became the Constitution of 1840, the first written constitution ever granted to the people of Hawaiʻi.

Takeover of the Kingdom

In 1843, three years after the signing of the constitution, the kingdom suffered a serious blow. With his shipʻs cannons pointing at Honolulu, British Captain Lord George Paulet seized control of the Hawaiian kingdom. He claimed this action was necessary to protect the rights of British residents in the islands. On February 25, 1843, the Hawaiian flag was lowered and the British flag hoisted in its place. He saw the fear, anger and confusion among his people. However, to avoid any loss of life, he had to give in to Paulet. Kauikeaouli assured his people that the kingdom would be restored once the British government learned about the forceful takeover.

Restoration of the Kingdom

Five months later, on July 31, 1843, the kingʻs hope for the return of the Hawaiian monarchy came true. With the help of British Admiral Richard Thomas, the Hawaiian flag was once again raised over the islands. The kingdom was restored! Kamehameha III spoke the words that became the motto of the state of Hawaiʻi: "Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono." This has most commonly been translated as: "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness." The celebration continued for ten days. For years following that first celebration, Kauikeaouli made Restoration Day, July 31, the most important holiday of the year.

Recognition of Independence

Kauikeaouli wanted his kingdom to have a more secure and respected place in the world. He wrote letters to the president of the United States, the queen of Great Britain and the king of France. Kamehameha III wanted the leaders of these countries to recognize the independence of the Hawaiian kingdom. The letters were to be delivered in person to an official of each nation. Three representatives from the kingʻs government were chosen to undertake this mission. They left the islands in 1842. Upon their arrival in each country they presented the letters to officials of the country. They then held discussions on the need for formal recognition of the Hawaiian kingdom. They also asked for treaties equally favorable to each of the nations involved. In 1844 agreements were reached. The United States, Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian kingdom as an independent nation. Hawaiʻi was a member of the "family of nations." From then on treaties with other countries could be developed on a more equal basis.

The Hawaiian Belief

The idea of owning the ʻāina (land) was hard for Hawaiians to grasp. In Hawaiian culture no individual owned land-it belonged to the akua (gods). The mōʻī (king) and his aliʻi nui (high chiefs) controlled the land while the konohiki (lesser chiefs) managed it. The makaʻāinana lived on the land. In return they gave the aliʻi nui their service and a portion of what they produced.

The Land Commission

Although Kauikeaouli and his chiefs tried to keep Hawaiian land from being sold to foreigners, it was not to be. Foreigners continued to complain and demand changes. In 1845, acting upon the advice of a few trusted foreigners, the king created a "Land Commission." The Land Commission was a five-member committee appointed to study the land claims of both Hawaiians and foreigners. Their decisions would be final. What happened during the next five years would change the land system in Hawaiʻi forever.

The Māhele

On January 27, 1848, the Māhele, or division of lands, began. With the Māhele the foreign concept of "land ownership" was established in Hawaiʻi.

The Kuleaiia Act of 1850

As for the makaʻāinana, the Kuleana Act of August 1850 made it possible for them to own land in fee simple. Kuleana is the Hawaiian word for responsibility. Therefore kuleana also became the term for land that people had lived on and cultivated.

The Constitution of 1852

By 1852 Kamehameha III realized that the Constitution of 1840 was out of date. The responsibilities of the government had greatly increased so a new constitution was written to meet those responsibilities.

The Constitution of 1852 was more liberal, or generous, than the Constitution of 1840. It gave greater power to the people in running the government. By his actions, Kamehameha III gave up much of the monarchʻs power. Never again would a Hawaiian ruler have the power his father, Kamehameha I, once had. The Constitutions of 1840 and 1852 changed the structure of Hawaiian government forever.

Threats to Hawaiʻiʻs Peace and Security

In 1844 the United States, Great Britain and France had recognized the Hawaiian kingdom as an independent nation. Unfortunately, this recognition did not bring the peace and security Kamehameha III had hoped for. Several events at this time caused the king and his people to feel uneasy and uncertain about the future.

Declining Hawaiian Population

Adding to Kauikeaouliʻs worries was the declining health and population of his people. When Captain Cook arrived in the islands, in 1778, there were about three hundred thousand Hawaiians. In 1825, the year Kauikeaouli became king, there were only half as many, or about one hundred fifty thousand Hawaiians. Tens of thousands had died from diseases brought by foreigners. To make matters worse, a smallpox epidemic broke out on Oʻahu in 1853- Smallpox is a highly contagious disease. Kamehameha III was alarmed at how fast his people were dying! Even though he tried to quarantine, or separate, the sick from the healthy, twenty-five hundred Hawaiians died in the epidemic. By 1854 there were only seventy thousand Hawaiians left in the kingdom. Meanwhile the foreign population in Hawaiʻi continued to grow.

Death of Kamehameha III

King Kamehameha III, Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa Kuakamanolani Mahinalani Kalaninuiwaiakua Keaweaweʻulaokalani, died on December 16, 1854. He had been in poor health for more than a year. Kauikeaouli was only forty years old. The Hawaiian people were deeply saddened.

"A Kingdom of Learning"

"Chiefs and people, give ear to my remarks! My kingdom shall be a kingdom of learning." These words, spoken by Kauikeaouli, showed he believed that education was very important. He believed education would prepare his people for the changes taking place in Hawaiʻi.

The Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School

In 1839 Kauikeaouli opened the Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School in Honolulu. He felt that future rulers must be prepared to rule a kingdom which now included both Hawaiians and foreigners. The Chiefsʻ Childrenʻs School was a very special school. In 1846 its name was changed to the Royal School. Only sixteen Hawaiian children of the highest chiefly rank attended the Royal School. Five of them later became rulers of the kingdom.

Public Education

Recognizing the growing importance of education, the government took over direction and support of the schools. The Constitution of 1840 provided for free public education and required all children to attend school. By 1850 English was the language used in business, government and foreign relations. Many Hawaiians wanted to have their children learn English, hoping this would prepare them for a better future. Toward the end of Kauikeaouliʻs reign there were 423 schools in Hawaiʻi with an enrollment of over twelve thousand students. This greatly pleased Kamehameha III. His kingdom had indeed become a "kingdom of learning."

A Constitutional Government

The Declaration of Rights-1839

One of the first changes made by Kamehameha III took place in government. Kamehameha III was convinced that all people should have certain rights. In 1839 he put these rights in writing in a document called The Declaration of Rights.

The Constitution of 1840

The next year an even more important event happened. Kamehameha III granted his people laws which, for the first time, explained in writing how the government would be run. These special laws became the Constitution of 1840, the first written constitution ever granted to the people of Hawaiʻi.

Takeover of the Kingdom

In 1843, three years after the signing of the constitution, the kingdom suffered a serious blow. With his shipʻs cannons pointing at Honolulu, British Captain Lord George Paulet seized control of the Hawaiian kingdom. He claimed this action was necessary to protect the rights of British residents in the islands. On February 25, 1843, the Hawaiian flag was lowered and the British flag hoisted in its place. He saw the fear, anger and confusion among his people. However, to avoid any loss of life, he had to give in to Paulet. Kauikeaouli assured his people that the kingdom would be restored once the British government learned about the forceful takeover.

Restoration of the Kingdom

Five months later, on July 31, 1843, the kingʻs hope for the return of the Hawaiian monarchy came true. With the help of British Admiral Richard Thomas, the Hawaiian flag was once again raised over the islands. The kingdom was restored! Kamehameha III spoke the words that became the motto of the state of Hawaiʻi: "Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono." This has most commonly been translated as: "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness." The celebration continued for ten days. For years following that first celebration, Kauikeaouli made Restoration Day, July 31, the most important holiday of the year.

Recognition of Independence

Kauikeaouli wanted his kingdom to have a more secure and respected place in the world. He wrote letters to the president of the United States, the queen of Great Britain and the king of France. Kamehameha III wanted the leaders of these countries to recognize the independence of the Hawaiian kingdom. The letters were to be delivered in person to an official of each nation. Three representatives from the kingʻs government were chosen to undertake this mission. They left the islands in 1842. Upon their arrival in each country they presented the letters to officials of the country. They then held discussions on the need for formal recognition of the Hawaiian kingdom. They also asked for treaties equally favorable to each of the nations involved. In 1844 agreements were reached. The United States, Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian kingdom as an independent nation. Hawaiʻi was a member of the "family of nations." From then on treaties with other countries could be developed on a more equal basis.

The Hawaiian Belief

The idea of owning the ʻāina (land) was hard for Hawaiians to grasp. In Hawaiian culture no individual owned land-it belonged to the akua (gods). The mōʻī (king) and his aliʻi nui (high chiefs) controlled the land while the konohiki (lesser chiefs) managed it. The makaʻāinana lived on the land. In return they gave the aliʻi nui their service and a portion of what they produced.

The Land Commission

Although Kauikeaouli and his chiefs tried to keep Hawaiian land from being sold to foreigners, it was not to be. Foreigners continued to complain and demand changes. In 1845, acting upon the advice of a few trusted foreigners, the king created a "Land Commission." The Land Commission was a five-member committee appointed to study the land claims of both Hawaiians and foreigners. Their decisions would be final. What happened during the next five years would change the land system in Hawaiʻi forever.

The Māhele

On January 27, 1848, the Māhele, or division of lands, began. With the Māhele the foreign concept of "land ownership" was established in Hawaiʻi.

The Kuleaiia Act of 1850

As for the makaʻāinana, the Kuleana Act of August 1850 made it possible for them to own land in fee simple. Kuleana is the Hawaiian word for responsibility. Therefore kuleana also became the term for land that people had lived on and cultivated.

The Constitution of 1852

By 1852 Kamehameha III realized that the Constitution of 1840 was out of date. The responsibilities of the government had greatly increased so a new constitution was written to meet those responsibilities.

The Constitution of 1852 was more liberal, or generous, than the Constitution of 1840. It gave greater power to the people in running the government. By his actions, Kamehameha III gave up much of the monarchʻs power. Never again would a Hawaiian ruler have the power his father, Kamehameha I, once had. The Constitutions of 1840 and 1852 changed the structure of Hawaiian government forever.

Threats to Hawaiʻiʻs Peace and Security

In 1844 the United States, Great Britain and France had recognized the Hawaiian kingdom as an independent nation. Unfortunately, this recognition did not bring the peace and security Kamehameha III had hoped for. Several events at this time caused the king and his people to feel uneasy and uncertain about the future.

Declining Hawaiian Population

Adding to Kauikeaouliʻs worries was the declining health and population of his people. When Captain Cook arrived in the islands, in 1778, there were about three hundred thousand Hawaiians. In 1825, the year Kauikeaouli became king, there were only half as many, or about one hundred fifty thousand Hawaiians. Tens of thousands had died from diseases brought by foreigners. To make matters worse, a smallpox epidemic broke out on Oʻahu in 1853- Smallpox is a highly contagious disease. Kamehameha III was alarmed at how fast his people were dying! Even though he tried to quarantine, or separate, the sick from the healthy, twenty-five hundred Hawaiians died in the epidemic. By 1854 there were only seventy thousand Hawaiians left in the kingdom. Meanwhile the foreign population in Hawaiʻi continued to grow.

Death of Kamehameha III

King Kamehameha III, Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa Kuakamanolani Mahinalani Kalaninuiwaiakua Keaweaweʻulaokalani, died on December 16, 1854. He had been in poor health for more than a year. Kauikeaouli was only forty years old. The Hawaiian people were deeply saddened.

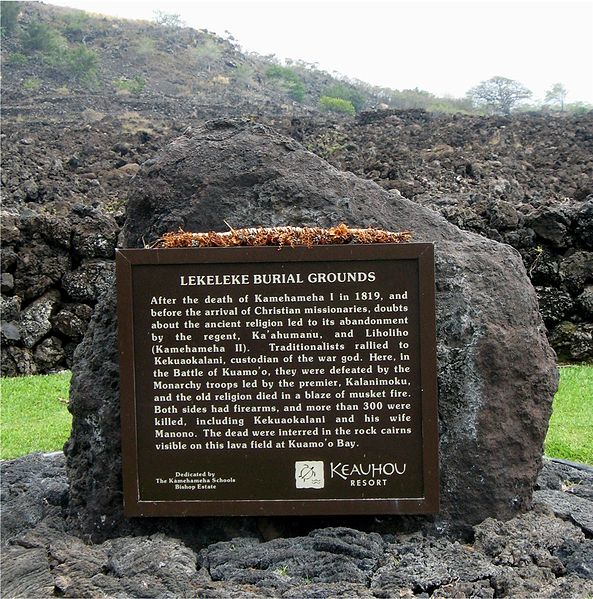

Kuamo'o Bay and the Battlefield of Lekeleke

Battlefield of Lekeleke

Lekeleke Burial Ground, also known as the Kuamo'o Burials, is a historic battlefield and burial site located on Kuamo'o Bay in the North Kona District on the Big Island of Hawaii. Over 300 warriors were killed on the site during the epic Battle of Kuamo'o. The area is listed on the Hawaii register of historic places, as well as in the National Register of Historic Places. Kuamo'o is historically significant because it is the site of the bloody battle between two powerful cousins, Kekuaokalani and Liholiho (Kamehameha II) in 1819. Kekuaokalani and his wife, Manono, gallantly led the fight to preserve traditional ways, but were ultimately defeated by the forces of Liholiho who were seeking to end the ancient Hawaiian religious system called the KapuWestern rifles were used by both factions which contributed to the high death toll. Today, terraced graves on this lava field serve as memorials to the hundreds of warriors who fell during the battle. Ti leaves, wrapped around lava stones, are offered on the graves by native Hawaiians.

A plaque on a boulder explains the circumstances of the battle and how over 300 were killed. Following the death of Kamehameha I in 1819, King Kamehameha II (Liholiho) declared an end to the kapu system. Forty years had passed since the death of Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay, during which time it became increasingly apparent to the chiefly classes that the kapu system was breaking down; social behavior was changing rapidly and western actions clearly were immune to the ancient Hawaiian kapu (taboos). Kamehameha II sent word to the island districts, and to the other islands, that the numerous heiau and their images of the gods be destroyed. Kekuaokalani (Kamehameha II’s cousin) and his wife Manono opposed the abolition of the kapu system and assumed the responsibility of leading those who opposed its abolition. Kekuaokalani demanded that Kamehameha II withdraw his edict on abolition of the kapu system. Kamehameha II refused. The two powerful cousins engaged at the final Hawaiian battle of Kuamo`o, the king's better‐armed forces, led by Kalanimoku, defeated the last defenders of the Hawaiian gods, of their temples and priesthoods.

A plaque on a boulder explains the circumstances of the battle and how over 300 were killed. Following the death of Kamehameha I in 1819, King Kamehameha II (Liholiho) declared an end to the kapu system. Forty years had passed since the death of Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay, during which time it became increasingly apparent to the chiefly classes that the kapu system was breaking down; social behavior was changing rapidly and western actions clearly were immune to the ancient Hawaiian kapu (taboos). Kamehameha II sent word to the island districts, and to the other islands, that the numerous heiau and their images of the gods be destroyed. Kekuaokalani (Kamehameha II’s cousin) and his wife Manono opposed the abolition of the kapu system and assumed the responsibility of leading those who opposed its abolition. Kekuaokalani demanded that Kamehameha II withdraw his edict on abolition of the kapu system. Kamehameha II refused. The two powerful cousins engaged at the final Hawaiian battle of Kuamo`o, the king's better‐armed forces, led by Kalanimoku, defeated the last defenders of the Hawaiian gods, of their temples and priesthoods.

This changed the course of their civilization and ended the kapu system (and the ancient organized religion), effectively weakened belief in the power of the gods and the inevitability of divine punishment for those who opposed them, and made way for the transformation to Christianity and westernization. Here, at Lekeleke Burial Grounds, lay the remains of more than 300 warriors. Gaze upslope and see the terraced burials that mark this moment in history. The Journal of William Ellis (1823): Scene of Battle with Supporters of Idolatry After traveling about two miles over this barren waste, we reached where, in the autumn of 1819, the decisive battle was fought between the forces of Rihoriho (Liholiho), the present king, and his cousin, Kekuaokalani, in which the latter was slain, his followers completely overthrown, and the cruel system of idolatry, which he took up arms to support, effectually destroyed. The natives pointed out to us the place where the king’s troops, led on by Karaimoku (Kalanimoku), were first attacked by the idolatrous party. We saw several small heaps of stones, which our guide informed us were the graves of those who, during the conflict, had fallen there. We were then shewn the spot on which the king’s troops formed a line from the seashore towards the mountains, and drove the opposing party before them to a rising ground, where a stone fence, about breast high, enabled the enemy to defend themselves for some time, but from which they were at length driven by a party of Karaimoku’s (Kalanimoku) warriors.

Pu'u O' Hau and the Face of Pele

PU’U O’HAU Two cinder cones

the divide between North & South Kona.

This is Pele when she is mad! What makes Pele gets when people take lava rocks away from our island. Stones with letters and testimonies of horrible episodes are sent back to the islands daily by visitors who choose to test wrath of Pele. Don't do it.. but, if you do and strange things start to happen, don't send it back to me, send it directly to the Volcano National Park, they know what to do.

Legend of Pele the Fire Goddess and Ohia the Strong Handsome Man

A strong and handsome man named Ohia rejected the advances of Pele the fire goddess. She becomes enraged and in her fury Pele transforms Ohia into a hard wooded tree and separating him from his one and true love Lehua. Lehua was so heartbroken cries at the side of Ohia who is now a strong hard wooded tree. Lehua cry’s and cry’s by his side. The Gods look down and feel Lehua’s suffering and decide to transform her into a blossom and attaches her to Ohia so that they will be together for all time. So today when someone picks the flowers of the Lehua they separating her from the Ohia and it begins to rain. For this is a reminder of the strong and undivided love of Ohia and Lehua.

The school children always say, Kumu (teacher) you have to say, “The End”

The school children always say, Kumu (teacher) you have to say, “The End”

The story teller plays an extremely important role in the Hawaiian culture.

Transferring historical events, Hawaiian traditions and values. Keeping everyone connected.

Makahiki

The Makahiki festival celebration was to give respect and honor to Lono the God of farming, fertility and peace. Makahiki marked a temporary stop to activities of war, hard labor and fighting. Beginning in late October or early November when the Pleiades constellation was first observed rising above the horizon at sunset, the Makahiki period continued for a little over three and a half months, through the time of rough seas, high winds, storms and heavy rains.

Makahiki to offer gifts of the land, a time to cease farming labors and a time to feast and enjoy competitive games. Hawaiians gave ritualized thanks for the abundance of the earth and called upon the gods to provide rain and prosperity in the future.

Lono, the god of fertility and rain, was identified with southerly storms. He is sometimes referred to as the elder brother of Pa`ao, the influential priest who also arrived from the south and who instituted new rituals and beliefs in the Hawaiian religion. Lono took many forms, or kino lau. He could be seen in the black rain clouds of kona storms, in flashing eyes that resembled lightning, or in kukui, a plant associated with the pig-god Kamapua`a. Kamapua`a and Pele were both close relatives of Lono. Pele was sometimes called Lono's niece, sharing his southern origins and favoring the rainy seasons and southern coasts for her eruptions.

The highest chief of the island acted as host to Lono during Makahiki, performing ceremonies to mark the beginning and end of the festival. The chief collected gifts and offerings – food, animals, kapa, cordage, feathers and other items – on behalf of Lono and redistributed them later amongst lesser chiefs and their followers. The chief declared the kapu on produce and the land which was observed as the Lono figure - a staff topped by a small carved figure and a crossbar supporting a white sheet of kapa – was carried around the island perimeter in a clockwise direction. Lono's retinue stopped at the boundary of each ahupua`a where a stone altar, or ahu, included the carved wooden pig - the pua`a - and where gifts of the district had been collected. The slow circuit of the island took several days.

Once all the tribute to Lono and the chief was collected, communities gathered to celebrate with feasts and games. Chiefs and commoners competed, as well as those trained as athletes. Boxing was a favorite spectator sport. Both men and women participated in the competitions; some contests were sham battles that resulted in death. Other games included `ulu maika (a type of bowling), foot races, marksmanship with pahe`e or short javelins, puhenehene, a guessing game with pebbles that often involved sexual wagers, wrestling and hula dancing. Hula – under guidance of the goddess Laka, sister to Pele – offered many chants and dances composed specifically for Makahiki. They honored Lono, the chief, Kane (the god most closely associated with taro), and were meant to invoke rain and fertility.

In addition to the games and circuit of the Lono figure, the chief observed further religious ceremonies. Makahiki rituals were the most festive of the Hawaiian religion and included dramatic pageants and other acted-out scenes. The pageant of Kahoali`i honored a mythical hero sometimes associated with the dark underworld where the sun goes at dusk. The pageant of Maoloha, or the net of Makali`i, featured a net of food symbolizing the Pleiades and a future period of prosperity. Once the proper rituals and ceremonies were performed, the chief lifted the kapu on fishing, farming and war and a basket of food was ritually set adrift on the sea, lashed to the outrigger of a wooden canoe. Normal life resumed and the farming cycle began again.

Makahiki to offer gifts of the land, a time to cease farming labors and a time to feast and enjoy competitive games. Hawaiians gave ritualized thanks for the abundance of the earth and called upon the gods to provide rain and prosperity in the future.

Lono, the god of fertility and rain, was identified with southerly storms. He is sometimes referred to as the elder brother of Pa`ao, the influential priest who also arrived from the south and who instituted new rituals and beliefs in the Hawaiian religion. Lono took many forms, or kino lau. He could be seen in the black rain clouds of kona storms, in flashing eyes that resembled lightning, or in kukui, a plant associated with the pig-god Kamapua`a. Kamapua`a and Pele were both close relatives of Lono. Pele was sometimes called Lono's niece, sharing his southern origins and favoring the rainy seasons and southern coasts for her eruptions.

The highest chief of the island acted as host to Lono during Makahiki, performing ceremonies to mark the beginning and end of the festival. The chief collected gifts and offerings – food, animals, kapa, cordage, feathers and other items – on behalf of Lono and redistributed them later amongst lesser chiefs and their followers. The chief declared the kapu on produce and the land which was observed as the Lono figure - a staff topped by a small carved figure and a crossbar supporting a white sheet of kapa – was carried around the island perimeter in a clockwise direction. Lono's retinue stopped at the boundary of each ahupua`a where a stone altar, or ahu, included the carved wooden pig - the pua`a - and where gifts of the district had been collected. The slow circuit of the island took several days.

Once all the tribute to Lono and the chief was collected, communities gathered to celebrate with feasts and games. Chiefs and commoners competed, as well as those trained as athletes. Boxing was a favorite spectator sport. Both men and women participated in the competitions; some contests were sham battles that resulted in death. Other games included `ulu maika (a type of bowling), foot races, marksmanship with pahe`e or short javelins, puhenehene, a guessing game with pebbles that often involved sexual wagers, wrestling and hula dancing. Hula – under guidance of the goddess Laka, sister to Pele – offered many chants and dances composed specifically for Makahiki. They honored Lono, the chief, Kane (the god most closely associated with taro), and were meant to invoke rain and fertility.

In addition to the games and circuit of the Lono figure, the chief observed further religious ceremonies. Makahiki rituals were the most festive of the Hawaiian religion and included dramatic pageants and other acted-out scenes. The pageant of Kahoali`i honored a mythical hero sometimes associated with the dark underworld where the sun goes at dusk. The pageant of Maoloha, or the net of Makali`i, featured a net of food symbolizing the Pleiades and a future period of prosperity. Once the proper rituals and ceremonies were performed, the chief lifted the kapu on fishing, farming and war and a basket of food was ritually set adrift on the sea, lashed to the outrigger of a wooden canoe. Normal life resumed and the farming cycle began again.

Kealakehua Bay and the Captain Cook Monument

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaiʻi about 12 miles (19 km) south of Kailua-Kona. Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples (heiaus) and also includes the spot where the first documented European to reach the Hawaiian islands, Captain James Cook, died. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places listings on the island of Hawaii in 1973 as the Kealakekua Bay Historical District. The bay is a marine life conservation district in 1969.

Ancient history

Settlement on Kealakekua Bay has a long history. Hikiau Heiau was a luakini temple of Ancient Hawaii at the south end of the bay, associated with funeral rites. The large platform of volcanic rock was originally over 16 feet (4.9 m) high, 250 feet (76 m) long, and 100 feet (30 m) wide. The sheer cliff face called Pali Kapu O Keōuaoverlooking the bay was the burial place of Hawaiian royalty. The name means "forbidden cliffs of Keōua " in honor of Keōua Nui. He was sometimes known as the "father of kings" since many rulers were his descendants.

The village of Kaʻawaloa was at the north end of the bay in ancient times, where the Puhina O Lono Heiau was built, along with some royal residences. The name of the village means "the distant Kava", from the medicinal plant used in religious rituals. The name of the bay comes from ke ala ke kua in the Hawaiian Language which means "the god's pathway." This area was the focus of extensive Makahiki celebrations in honor of the god Lono. Another name for the area north of the bay was hale ki'i, due to the large number of wood carvings, better known today as "tiki".

Captain Cook and The King Of the Entire Island, Kalaniʻōpuʻu

Cook had entered the bay during Makahiki. This was a traditionally peaceful time of year, so he and his men were welcomed and given food. Cook and his crew stayed for several weeks, returning to sea shortly after the end of the festival. After suffering damage during a storm, the ships returned two weeks later, on February 14. This time relations were not as smooth.

After one of the crew members accused the Hawaiian men of Ka'awaloa of stealing one of the Resolution's small boats, Cook attempted to take the King Kalaniʻōpuʻu as hostage until the boat was returned.

Turmoil

When Kalaniʻōpuʻu died in 1782, his oldest son Kiwalaʻo officially inherited the kingdom, but his nephew Kamehameha I became guardian of the god Kūkaʻilimoku. A younger son, Keōua Kuahuʻula, was not happy about this and provoked Kamehameha. The forces met just south of the bay at the battle of Mokuʻōhai. Kamehameha won control of the west and north sides of the island, but Keōua escaped. It would take over a decade to consolidate his control.

In 1786, merchant ships of the King George's Sound Company under command of the maritime fur traders Nathaniel Portlock and Captain George Dixon anchored in the harbor, but avoided coming ashore. They had been on Cook's voyage when he was killed by natives. In December 1788, the Iphigenia under William Douglas arrived with Chief Kaʻiana, who had already traveled to China.

The first American ship was probably the Lady Washington around this time under Captain John Kendrick. Two sailors, Parson Howel and James Boyd, left the ship (in 1790 or when it returned in 1793) and lived on the island.

In March 1790, the American ship Eleanora arrived at Kealakekua Bay and sent a British sailor ashore named John Young, to determine whether the sister ship, the schooner Fair American, had arrived for its planned rendezvous. Young was detained by Kamehameha's men to prevent the Eleanora's Captain Simon Metcalfe from hearing the news of the destruction of the Fair American, and the death of Metcalfe's son, after the massacre at Olowalu. Young and Isaac Davis, the lone survivor of the Fair American, slowly adjusted to the island lifestyle. They instructed Hawaiians in the use of the captured cannon and muskets, becoming respected advisers to Kamehameha. In 1791 Spanish explorer Manuel Quimper visited on the ship Princess Royal.

More visitors

Priests traveling across the bay for first contact rituals, by John Webber

Main article: Vancouver Expedition George Vancouver arrived in March 1792 to winter in the islands with a small fleet of British ships. He had been a young midshipman on Cook's fatal voyage 13 years earlier and commanded the party that attempted to recover Cook's remains. He avoided anchoring in Kealakekua Bay, but met some men in canoes who were interested in trading. The common request was for firearms, which Vancouver resisted. One included chief Kaʻiana, who would later turn against Kamehameha. Vancouver suspected Kaʻiana intended to seize his ships, so left him behind and headed up the coast. There he was surprised to encounter a Hawaiian who in broken English introduced himself as "Jack", and told of traveling to America on a fur-trading ship. Through him, Vancouver met Keʻeaumoku Pāpaʻiahiahi, who gave him a favorable impression of Kamehameha (his son-in-law). He spent the rest of the winter in Oʻahu. Vancouver returned in February 1793; this time he picked up Keʻeaumoku and anchored in Kealakekua Bay. When Kamehameha came to greet the ship, he brought John Young, now fluent in the Hawaiian language, as an interpreter. This greatly helped to develop a trusted trading relationship. The Hawaiians presented a war game, which was often part of the Makahiki celebration. Impressed by the warriors' abilities, Vancouver fired off some fireworks at night to demonstrate his military technology.

Vancouver presented some cattle which he had picked up in California. Kamehameha placed a Kapu. a ten year law that forbid anyone from hurting or killing the cattle so they would multiple.

Ships in the bay (sketch by Rufus Anderson)Vancouver left in March 1793 after visiting the other islands to continue his expedition, and returned again January 13, 1794. He still hoped to broker a truce between Kamehameha and the other islands. His first step was to reconcile Kamehameha with Queen Kaʻahumanu. He dropped off more cattle and sheep from California, and discovered a cow left the year before had delivered a calf. The cattle became feral and eventually became pests. They were not controlled until the "Hawaiian Cowboys," known as the Paniolo, were recruited.

The ship's carpenters instructed the Hawaiians and the British advisers how to build a 36-foot (11 m) European-style ship, which they named the Britania. On February 25, 1794, Vancouver gathered leaders from around the island onto his ship and negotiated a treaty. Although this treaty was sometimes described as "ceding" Hawaii to Great Britain, the treaty was never ratified by British Parliament.

Decline

For the next few years, Kamehameha was engaged in his war campaigns, and then spent his last years at Kamakahonu to the north. By this time other harbors such as Lahaina and Honolulu became popular with visiting ships. By 1804, the heiau was falling into disuse. In 1814, a British ship HMS Forrester arrived in the midsts of a mutiny. Otto von Kotzebue arrived i 1816 on a mission from the Russian Empire.

When Kamehameha I died in 1819, his oldest son Liholiho officially inherited the kingdom, calling himself Kamehameha II. His nephew Keaoua Kekuaokalani inherited the important military and religious post of guardian of Kūkaʻilimoku. However, true power was held by Kamehameha's widow Queen kaʻahumanu. She had been convinced by Vancouver and other visitors that the European customs should be adopted. In the ʻAi Noa she declared an end to the old Kapu system.

Kekuaokalani was outraged by this threat to the old traditions, which still were respected by most common people. He gathered religious supporters at Kaʻawaloa, threatening to take the kingdom by force, as happened 37 years earlier. After a failed attempt to negotiate peace, he marched his army north to meet Kalanimoku's troops who were gathered at Kamakahonu. They met in the Battle of Kuamoʻo. Both sides had muskets, but Kalanimoku had cannon mounted on double-hulled canoes. He devastated the fighters for the old religion, who still lie buried in the lava rock.

The former village of Kaʻawaloa is now overgrown with Kiawe trees. The wood Kiʻi carvings were burned, and the temples fell into disrepair. A small Christian church was built in 1824 in Kaʻawaloa by the Hawaiian missionaries, and the narrow trail widened to a donkey cart road in the late 1820s, but the population declined and shifted to other areas.

In 1825, Admiral Lord Byron (cousin of the famous poet) on the ship HMS Blonde erected a monument to Cook and took away many of the old, sacred artifacts. The last royalty known to live here was high chief Naihe, known as the "national orator," and his wife Chiefess Kapiʻolani, early converts to Christianity. In 1829, she was saddened to see that the destruction of the temples included desecrating the bones of her ancestors at the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau. She removed the remains of the old chiefs and hid them in the Pali Kapu O Keōua cliffs before ordering this last temple to be destroyed. The bones were later moved to the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii in 1858, under direction of King Kamehameha IV.

In 1839 a massive stone church was built just south of the bay. It fell into ruin, and a smaller building called Kahikolu Church was built in 1852. This also fell into ruin, but has been rebuilt. In 1894 a wharf was constructed at the village at the south of the bay, now called Napoʻopoʻo. A steamer landed in the early 20th century when Kona coffee became a popular crop in the upland areas.

A large white stone monument was built on the north shore of the bay in 1874 on the order of Princess Likelike and was deeded to the United Kingdom in 1877. The chain around the monument is supported by four cannon from the ship HMS Fantome; they were placed with their breaches embedded in the rock in 1876. It marks the approximate location of Cook's death.

About 180 acres around the bay was designated a State Historic Park in 1967, and it was added as a Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The 315 acres of the bay itself were declared a Marine Life Conservation District in 1969.

Ancient history

Settlement on Kealakekua Bay has a long history. Hikiau Heiau was a luakini temple of Ancient Hawaii at the south end of the bay, associated with funeral rites. The large platform of volcanic rock was originally over 16 feet (4.9 m) high, 250 feet (76 m) long, and 100 feet (30 m) wide. The sheer cliff face called Pali Kapu O Keōuaoverlooking the bay was the burial place of Hawaiian royalty. The name means "forbidden cliffs of Keōua " in honor of Keōua Nui. He was sometimes known as the "father of kings" since many rulers were his descendants.

The village of Kaʻawaloa was at the north end of the bay in ancient times, where the Puhina O Lono Heiau was built, along with some royal residences. The name of the village means "the distant Kava", from the medicinal plant used in religious rituals. The name of the bay comes from ke ala ke kua in the Hawaiian Language which means "the god's pathway." This area was the focus of extensive Makahiki celebrations in honor of the god Lono. Another name for the area north of the bay was hale ki'i, due to the large number of wood carvings, better known today as "tiki".

Captain Cook and The King Of the Entire Island, Kalaniʻōpuʻu